The disturbing discovery added to the hospital’s already notorious reputation. Since its beginnings in the 19th century, the Salem hospital had been plagued with allegations of abuse and inhumane therapies. It was famously used as the set of the 1975 movie One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, a film that, among other things, explored the darker side of mental-health facilities of its time.

The remains were of people who died between 1913 and 1971. They were cremated at the hospital and for various reasons the ashes were not claimed. The canisters were moved from one location to another on hospital grounds and eventually, forgotten.

Most were residents at the Oregon State Hospital, though a few were employees. Because the hospital had the nearest crematorium in the region, some were residents of the Oregon State Penitentiary, Oregon State Tuberculosis Hospital, and other nearby facilities.

State and hospital officials understood the gravity of their discovery and moved to give these remains a more appropriate and respectful resting place, and if possible connect them with living relatives. As of January 2021, the hospital has reunited the cremated remains of 699 people with family members and descendants.

In 2007, The Oregon Legislature authorized publication of the names attached to the cremains in an effort to get more of them claimed. The Oregonian’s Pulitzer Prize-winning series “Oregon’s Forgotten Hospital” brought national attention to the cremains, which led to some initial connections with relatives. However, the real key to connecting the cremains to family members has been an amateur genealogist in Roseburg, Phyllis Zegers.

What’s surprising is how many people were committed to the Salem State Hospital for issues we would not consider a mental illness today.

Since 2014, Zegers has researched over 3,360 unclaimed cremains and helped reunite most of those 699 containers of ashes with family members.

Originally, she had been researching her own family, including a distant cousin who’d been institutionalized at Oregon State Hospital in the 1890’s. “I was interested in what her experience had been, and as I looked into her and the hospital, I ran across information about the unclaimed cremains and I found that so fascinating,” said Zegers. “From there I kind of darted off and decided I wanted to research these people.”

Her original plan was to honor each individual by writing their biographies and posting them on “Find A Grave,” an online database of cemetery records owned by Ancestry.com.

“In writing biographies, I felt like I needed to learn about their parents, their siblings, their children,” said Zegers. “While doing that research, I found that I could find living relatives fairly easily.”

It may have seemed easy for Zegers, but the hospital staff found her work invaluable. “We couldn’t have done this without her,” said Joni DeTrant, Health Information Manager and Records Custodian for OSH and the Oregon Health Authority. “Before Phyllis, we just didn’t have the time to do the kind of reverse-genealogy this requires.”

Contacting strangers about their long-lost relatives is a sensitive task in any situation, perhaps especially if the relative is also connected to a famous mental institution. Zegers approaches her contacts with compassion and the added warmth of a handwritten letter. With the letter, she includes biographical information she’s acquired, a death certificate, and the information needed to collect the cremains. Then she waits.

“I try to give folks time to process, because sometimes these letters and this information don’t land softly,” she said. “Emotions range from shock to embarrassment. It also can open the floodgates to a lot of family secrets.”

Zegers says that, with the stigma connected with mental illness, sometimes people were “disappeared” from their family. “Relatives are told that the person hopped a freight to some unknown place or that they died,” she said. “Other times, they are just never mentioned. People I talk to will say, no one told us about that aunt or cousin, or even a brother or sister. It’s really heartbreaking sometimes.”

For relatives of those with mental health issues, Zegers says, learning about the cremains can be a revelation. “People will often say ‘Oh, that explains so much, or this mental illness is repeated throughout my family.’” When these stories come to light, says Zegers, some people are better able to understand their own mental health and to talk about it. “We need to be more open about mental health. Hiding it or being ashamed hurts everyone,” she said.

Part of Zegers’ motivation in returning the cremains to relatives is to help restore the humanity that so many of these people weren’t afforded in their lives. “These people weren’t just their mental illness or their disability or their crime. They were real people with families and lives,” she said.

Zegers says she’s often moved by the relatives of the people who came from the state penitentiary. “Sometimes these were pretty rough characters. I’m always very impressed with the relatives who say things like, ‘Yes, he did some heinous thing, but he was once an innocent child and has humanity, so I want to claim his ashes,” she said.

Since 2014, Zegers has researched over 3,360 unclaimed cremains and helped reunite most of those 699 containers of ashes with family members.

What’s surprising in some ways, says Zegers, is how many people were committed to the Salem State Hospital for issues we would not consider a mental illness today.

“A lot of people were institutionalized for what we know now is Alzheimer’s or dementia, but there were people who were committed for strange reasons,” she said. For example, the cousin that Phyllis was researching was institutionalized in the 1890’s for something called “overstudy,” which some online searches found defined as a sort of fatigue that affected busy society women, the overworked, or businessmen. Overstudy was also called Neurasthenia and nicknamed “Americanitis.” Other documented reasons for institutionalization included “Financial Worry” or “Religion.”

Pipelines to the State Hospital

In the past, Zegers said, it was very easy to commit people to psychiatric institutions, especially women. Husbands would often use it to get rid of an unwanted wife. “If you didn’t like to do housework you could get institutionalized,” Zegers said.

“A lot of the diagnoses had a sexual aspect to them,” said Zegers. “Women could be committed for masturbation or promiscuity. Others were institutionalized for syphilis, which was often also listed as the cause of death.”

There was even a separate institution called the Cedars near Troutdale, where, during WWII, women with venereal diseases were held. The idea, says Zegers, wasn’t so much to treat the women as to keep the soldiers away from them. “It was part of the war effort, to protect the soldiers,” she said. “While it wasn’t directly connected to OSH, a lot of those women ended up at the OSH in the end,” she said.

Other OSH residents also came from Edgefield, the Multnomah County Poor Farm. “Lots of folks that ended up at the Oregon State Hospital were transferred from Poor Farms or Poor Houses across the state,” said Zegers. “Poor houses were basically a pipeline to the state hospital.”

Real people with real lives

Through her research, Zegers says she’s learned a lot about Oregon and the people who have lived here. “It’s amazing to get a glimpse of these people’s lives, their skills or successes, their good luck and bad luck,” she said. “Sometimes it’s a window into Oregon history. For example, the daughter of one of Oregon’s first treasurers was institutionalized at OSH.” Zegers wrote a biography of her that offers a snapshot of Oregon’s early politicians:

Ella was born in Salem, Oregon in March 1858. Her father, Rev. John Daniel Boon (a distant relative of the more famous Daniel Boon) was among the earliest white settlers, and first homesteaded in Oregon’s Willamette Valley. In 1851, Ella’s father was elected by the Legislature to the position of Territorial Treasurer and in 1858 he was elected to be the first State Treasurer when Oregon took statehood in the following year. The treasury was operated out of his general store built in Salem on what was called Boon’s Island. Boon Brick Store is now a pub known as McMenamins Boon’s Treasury. Ella Boon was widowed and later remarried and divorced in California. She was admitted to OSH in 1905, and she died there 14 years later.

Zegers says she sometimes gets drawn to certain people or groups of people who’ve made a mark in history, such as early women’s rights activists. “I do have a particular fondness for the suffragettes,” she said. “They have such great stories. I think they’ve all found a home, so that’s good,” she said.

Dr. Nina Wood

Suffragette and activist Nina Evaline Wood’s cremains were claimed just last year. Born in 1861 she moved with her family from Wisconsin to the Pacific Northwest in the 1870’s.

Nina worked all her adult life. In 1890 she homesteaded 160 acres of land south of Spokane, Washington. She also earned a medical license, and in 1891 she was on the staff and board of trustees at the Washington Biochemic Medical College in Spokane. Her specialty was herbalism and therapeutics.

Wood was one of the founding members of the “Women’s Protective Association of Spokane,” a group of women who were outraged over the treatment of rape victims in Spokane’s legal system. It’s possible her work with the legal system inspired her to become an attorney. In 1896, she was the sole woman in a class of 74 students to take and pass the Oregon Law Exam in Salem.

News articles referred to her as the “woman lawyer” and “a woman socialist who claims to be a member of the Portland bar.” Wood wrote booklets and gave speeches in support of socialism. She also advocated for humane practices in prisons, international peace, child safety, and child labor laws.

Women won the right to vote in Washington in 1910, in California in 1911, and in Oregon in 1912. In March 1913, Woods was among the first women in Oregon to register to vote. She then began working towards national women’s suffrage because most other states had not yet passed legislation that allowed women the right to vote. Nationally, women did not have the right to vote until the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920. Woods continued to fight for world peace, women, and the poor well into her old age. She was admitted to OSH in 1930 and died a year and half later. The cause of death was an ovarian cyst and “senile psychosis.”

For some individuals, Zegers says the search is ongoing. “There are a few people, whose stories hit me hard and I hope I can get them home to a family member,” she said.

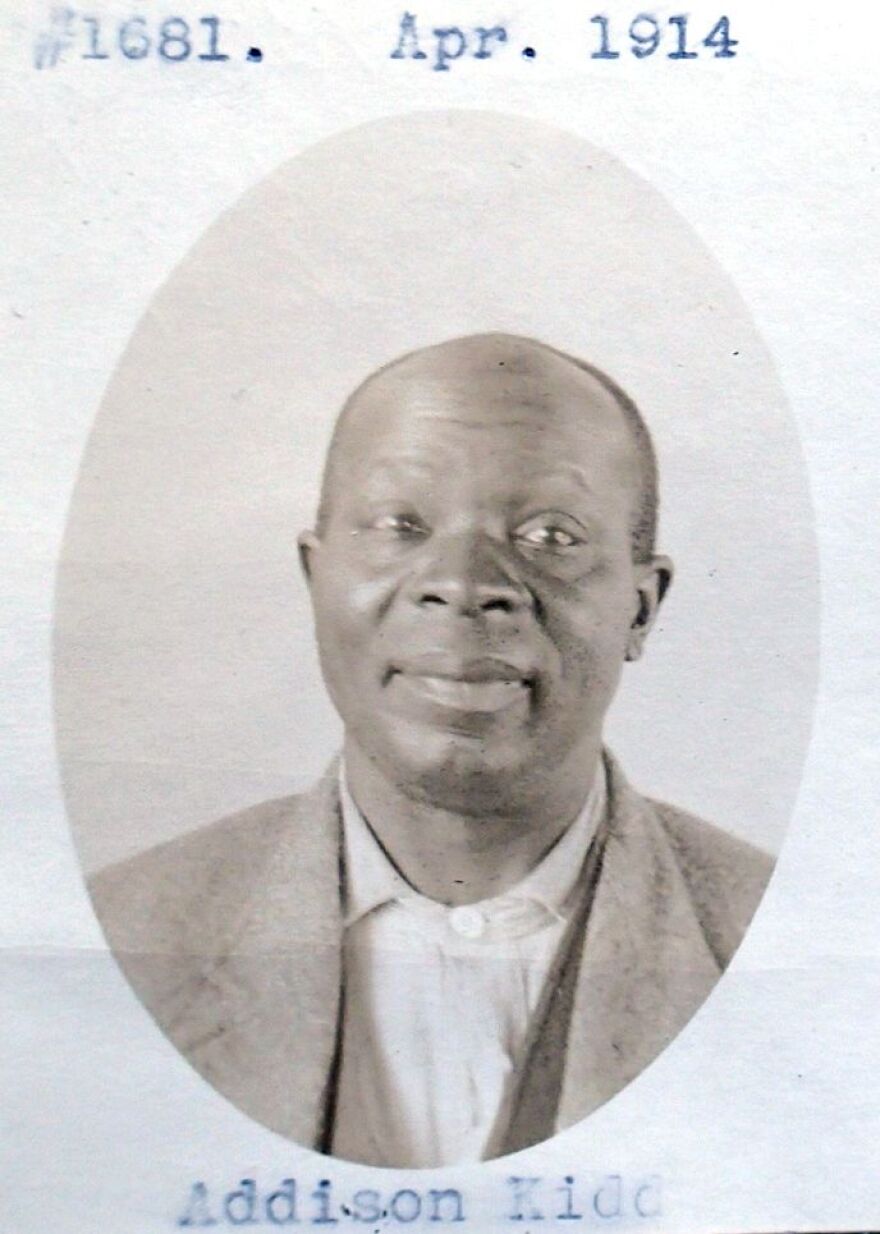

One such soul is Addison Kidd, a resident at the penitentiary who was transferred to the OSH in 1904. “I’m really invested in him, said Zegers. “The horrible treatment he experienced at the penitentiary broke my heart. I really wanted him to get back to his family, but he still hasn’t been claimed.” There’s not a lot of information about his relatives, but Zegers did find he likely had some great-nieces and nephews, Dellanna, James, Martha, Iva, Cherry and Jesse, in the 1920’s.

Addison Kidd

Kidd, who was African-American, was born in Mississippi shortly before the Civil War in 1870.

Kidd was transient and “rode the rails” to Oregon. He was sentenced to life in the Oregon State Penitentiary in 1902 for placing bolts on a railroad track, which resulted in the death of an engineer. In prison, Kidd was punished for things such as laughing, singing, whistling, and “pretending to be insane.” His punishments included being placed in solitary confinement, chained to a door or post for 8–12 hours, and having his foot put in what was called an “Oregon Boot” — a metal shackle weighing 5–28 pounds placed on the foot of prisoners to limit their mobility and stability. By 1904, Kidd had stopped talking or singing and was practically catatonic. At some point he was transferred to the OSH, where he died in 1931. In 1935, records of brutal prison punishments were made public. Kidd’s frequent punishments were among those listed.

The Find-a-Grave website allows people to leave comments, remembrances or virtual flowers. So far, over the past two years only Zegers has left “flowers” and wishes for a peaceful rest to Kidd and many of the other unclaimed remains.

Another person whose remains have yet to be claimed endured three years at a Japanese internment camp during WWII, and died at OSH of complications from the tuberculosis he likely caught while interred.

Tokutaro Nagaoka

Tokutaro Nagaoka was a first-generation immigrant from Japan, living near Portland in Boring, Oregon and working as a farm laborer

After the attack on Pearl Harbor President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered Japanese-Americans in the U.S. to be incarcerated in concentration camps. The internment had more to do with the country’s racism than any true security concerns posed by Japanese Americans. Between 110,000 and 120,000 Japanese people were held in camps.

Tokutaro was among those assigned to the Minidoka detention center near Eden and Twin Falls in southern Idaho.

In 1945, Tokutaro was released and went to Portland. Almost 69% of Japanese Americans in Oregon returned to their former hometowns, but they often faced campaigns to exclude them from their communities.

Tokutaro was admitted to the Oregon State Hospital in 1957. At some point he had contracted tuberculosis that was in remission. TB was common where people were living in large numbers in close quarters. Tokutaro died there 3 years later of heart disease. He was 79 years old.

Zegers says she’s often struck by the fascinating stories of these people’s lives. “Some could be novels or movies,” said Zegers. “Others were simple lives that ended sadly, but they were all human and deserve to be remembered.”

She recently returned the cremains of the grandmother of famed poet and writer Sylvia Plath. “Ernestine Plath’s son Otto was living in Seattle when he had his mother committed,” she said.

“Ernestine died at OSH in 1919 and her ashes were unclaimed until last year. During my research, I found that Otto Plath had a Wikipedia page, which linked him to his daughter Sylvia,” said Zegers.

Sylvia Plath often wrote about her struggles with depression and eventually committed suicide. “I don’t know how much Sylvia may or may not have known about her grandmother, but understanding those family links can be comforting and show you that you aren’t the only one struggling,” said Zegers.

Zegers says she likes it when her research falls into place the way Ernestine Plath’s did, where a Google search leads from one person to another until she can connect the cremains to a living relative. “It’s like a puzzle and really satisfying,” she said.

Recently, Zegers was awarded a 2020 Oregon Heritage Excellence Award by the Oregon Historical Society for her work researching and reuniting the cremains.

Zegers says one of her favorite aspects of the work is hearing from the living relatives what it means to them to receive the ashes and how it helped them connect with other family members. “It’s really sweet seeing what happens with the living afterward. It’s meaningful when they take it to another level,” she said. “I love hearing what doors this opens for living people. That’s the core joy for me.”

Angela Decker joined JPR in 2016 after a long history in print journalism. She’s a JPR host of Morning Edition and also a co-producer of the Jefferson Exchange, uncovering interesting topics and booking guests to discuss them. When she’s not at JPR, Angela is a freelance writer and part-time poet. She’s the mother of two hungry teens and too many pets.